Apalachicola River, Photo credit: Isaac Lang

Rights of the Rivers

(This is a slightly revised version of a keynote talk I presented at the annual gathering of the Apalachicola Riverkeepers on 3/26/16. It’s longer than usual!)

You cannot live in the Southeast without noticing how rivers define the places where we live. They bring us fresh water and so much more, but their geographical delineations of bioregion are among their most magical qualities. I first noticed how the rivers embrace us in the early 1990s, when I traveled often to south Florida, learning about swallow-tailed kites.

But as essential these waterways are–to who we are as humans–some rivers nevertheless become ghosts.

Several times a year, I fly to the west coast to visit my beloved son David, who attends medical school, and his fiancée Hannah, in Los Angeles. The last leg of the long flight takes me over the San Gabriel Mountains and then down into the Los Angeles basin. Always, I am struck when I see what remains of the Los Angeles River.

Once upon a time, an underground aquifer in the San Fernando Valley and the surrounding mountains, fed the headwaters of Los Angeles River, which in turn created a lush coastal plain. Today, the river is largely encased in concrete and hardly recognizable. After catastrophic flooding, Congress authorized the Army Corps of Engineers to tame the Los Angeles in 1934. They encased three-quarters of the river in a concrete ditch, fixing it once and for all in its current—artificial—path.

From above, it appears to be an irrigation canal or a “water freeway” at the base of gray concrete slabs. It saddens me when I see it from the window of a plane.

But I also sense that the Los Angeles River is still a reality, holding its potential, waiting for its waters to be returned. Waiting for its needs to be honored so that it may again breathe in and out, up-and-down, with seasonal rainfall and even tidal movement, as all coastal rivers are born to do.

It’s very, very clear, when you consider the Los Angeles River, that it is not the river that is broken, but rather the human relationship to it, that has caused the near death of this ancient waterway.

It touches me deeply to learn of the field trips and the passionate advocacy that some Los Angelenos have undertaken on behalf of their wounded water. And it is encouraging to learn that small mileages of that river are being restored.

From Georgia to the Gulf

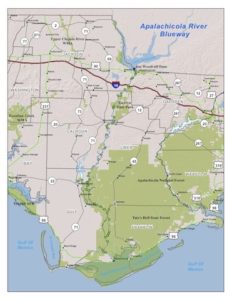

Let’s consider our River, our powerful Apalachicola, the western boundary of north Florida’s Red Hills and Gulf Coastal Bioregions.

The River is the sum of the rivers pouring into her body (the Flint and Chattahoochee and Chipola and East), and a myriad of creeks, and bayous, and sloughs, and springs (such as Owl and Spring and Graham and Cash and Whiskey George).

Think of all those waters blending and surrendering themselves into the Apalachicola. Think of how each of creek and bayou and slough loses its name and individual identity. And then, how the Apalachicola herself dives into the Gulf of Mexico, and seems to be lost. Now think of how those waters will rise again as fog and cloud, and eventually be reborn again as rain……..and river.

Next, let’s imagine as far back as we can to the source of the River, the physical source, and its source, in time.

Imagine a time when the Appalachian Mountains stood as tall as the Sawtooths are today. All that rock had to go somewhere….that’s what our beaches are made of.

Hundreds of millions of years ago, mountains as tall and rugged as the Sawtooth Range of the Idaho Rockies rose from the footprint of the Appalachian Mountains. Over unimaginably long eons, those granite peaks weathered into milky white quartz and dark feldspar–and sluiced down the rivers, first the Chattahoochee and the Flint. And then, at their confluence, the Apalachicola carried the sand down to the Gulf of Mexico, where it opened like a fist, showering and shaping ground up mountain sediment into brand new land.

Over time, as sea level rose and sand accrued, a circlet was formed around what we now call Apalachicola Bay. And: This River collaborated with the Gulf of Mexico and the rising sea, to create islands, an island chain so very precious to us: St. George, St. Vincent and Dog. I like to remember that when we cup a handful of white sand from the beach at St. George in our palms, we hold the bodies of mountains in our hands.

Apalachicola Bay, from the bridge to Eastpoint

The River has co-created so many beautiful species. She has developed a setting where millions of plants and animals thrive, in her channels, in her floodplains, and in her Bay. Most often, we think of how, in the embrace of warm, mocha Apalachicola Bay, generations of oyster larvae rooted themselves on layers upon layers of shell, thriving on the nutrients delivered from deepest Georgia. The River created conditions in Apalachicola Bay perfect for oysters to thrive, so perfect that 90 percent of all the oysters produced in Florida were once harvested here each year.

But in the Apalachicola, other beings beyond count or calculation were also born and died, their bones and teeth and fins and stems dissolving back into the Bay and the Gulf.

Some people may think of the River as inanimate. But when we look deeply, we can see that this is not mere water, not simply a commodity. The River has her own spirit and intelligence.

Photo credit: Shannon Lease

The Apalachicola is immense, beautiful, precious and unique in all time. When we travel on her body, rock on her current, we feel her perseverance and her equanimity. We know her power—taut and muscular and green, brown and warm and welcoming.

The River is not an object.

If we did assume that the River and her occupants: oysters, sturgeon, swallow-tailed kites, floodplain forests, kingfishers–if we did assume they are just a collection of objects, then we would believe they have no moral standing. And we would be wrong. In fact, it does not matter whether we think a particular species or river is important or natural or beautiful. We did not create them, and we do not own them. Earth’s creations have intention, agency, worth and rights, far beyond what we humans ascribe to them.

Visionary cultural historian Thomas Berry observed that humans created the concept of rights—and then awarded them all, to themselves. And that is the deep pathology of our time to consider our rights as human beings to be different from those of the rest of creation. This leads us to believe that we may take whatever we like, and it also lulls into thinking that our future is unrelated to the fate of the rivers, the shorebirds, or the islands.

Owl Creek, photo by Shannon Lease

It comes down to this: We have to change our whole relationship to the River. This requires that we look at her offerings as gifts, not resources. We are required to separate our needs from our wants, and to rein in the consumptive mindset that currently dominates our culture. We must continue to initiate conversations around the following question: How does the River sustain me, yes, but, more importantly, how do I sustain the river? As we do this, our reverence for the River will deepen.

It’s demanding and stressful work to be an activist in these times. We can feel trapped by the political and legal system that gives certain humans (and corporations), power over every other being “just because we said so.”

Where do we get the psychic energy we need to do this? How do we keep from being overwhelmed?

By remembering that we are not asked to succeed, but only to be faithful, to show up for the work!

By REMEMBERing, over and over again, that we are not separate, cannot be separate in any way from the planet.

And by believing that if we align ourselves with the true purposes of the Earth, and the River, we will know what to do, and have the strength to do it.

I’d like to leave you with a short poem by Adrienne Rich, in honor of the incredible work of Apalachicola Riverkeeper. I am proud to be a member, and I honor you.

“My heart is moved by all I cannot save

so much has been destroyed.

I have to cast my lot

with those who age after age,

perversely, with no extraordinary power,

reconstitute the world.”

Postscript: If you have read Coming to Pass: Florida’s Coastal Islands in a Gulf of Change, you will recognize some of this writing. I recommend to you the work of Thich Nhat Hanh, Kathleen Dean Moore, Miriam MacGillis, Joanna Macy and Thomas Berry, for their teachings about inborn rights. And if you are not already a member, please join the Apalachicola Riverkeepers. Learn all about their amazing work, and how you can help, at http://apalachicolariverkeeper.org/

Share On:

A touching portrayal of our relationship with nature!

Susan, your loving words were so comforting to me at Requiem for the Florida Black Bear.Your words moved me to tears as I read this article and I realize how much we have lost. Then comes the power of hope. Thank you♡

Patricia

Thank you for saying so, Patricia. That’s why I write.

Thanks, JC!

Sue, thank you for reminding me to comtemplate my deep relationship with rivers. As a selfish human I treasure rivers that have defined my life, the Suwannee and the Ausable, and all of the streams and rivers that I have had the opportunity to spend time with. I am reminded to ask myself, “what am I doing for these rivers who do so much for me?”

Audrey, any river you love has benefited from your mere presence🚣🏻. As have I…l

A fitting tribute to our waterways. A fine speech.

Thank you, Sue!

I hope so, Bonnie. I was so glad about the new CWAs, too! Lanark!!